Die Angst des Interviewten in Zeiten von Audio-Aufnahmegeräten ist unberechtigt, sagt Peter Laufer.

Manches, was den Österreichern selbstverständlich ist, ist anderen auffällig. So ging es fjum-Referent Peter Laufer, Journalist und Professor an der University of Oregon, bei Diskussionen über die Autorisierung von Interviews. Als Gastautor im Journo-Blog erklärt er, warum er diese bei uns so übliche Praxis ablehnt.

Auch wenn Sie Peter Laufer nicht zustimmen - stay tuned: In der nächsten Folge von Daniela Kraus' Journo-Blog argumentiert Lauren Kessler, Buchautorin und Leiterin des Studiengangs Multimedia Storytelling in Oregon, anders - aus der Perspektive der narrativen Journalistin.

Im Wortlaut: Peter Laufer über Interview-Autorisierung

What a lucky guy I am: I'm teaching the art and craft of journalistic interviewing here in Vienna to a cohort of students from the School of Journalism and Communication at the University of Oregon - where I am a professor - along with Austrian students of the Forum Journalismus und Medien (FJUM). Springtime (finally!) in Vienna. Where better than this crossroads of Europe to study the most basic journalism tool?

One of the key lessons in my interview course is that we journalists must exercise our distinct place in society. As grandiose as it may sound, we are guardians of democracy. Without us prying into affairs of state and business, culture and sport - the whole spectrum of human activity - society would collapse into an abyss of self-serving corruption, misinformation, disinformation and overall ignorance of current affairs.

Crime Against Journalism

Despite this critical role we journalists play, those about whom we report too often denigrate us. It is the old "blame the messenger" story. At the same time, we need access to newsmakers in order to report the news. Were it not human nature to want to talk - especially about ourselves and what we each perceive as our important activities - journalists would find it much more difficult to convince sources to open their mouths.

Still, journalists usually must solicit interview partners. We need to figure out with whom to speak in order to develop the facts and atmosphere needed to tell the stories we're reporting. Too often the result is that reporters act obsequious in the face of men and women in powerful societal positions. They "ask" for interviews. They allow the interviewee to "grant" them an opportunity to ask questions. And, as an ultimate crime against journalism, too often - especially here in Austria - journalists fold in the face of their interlocutors' inappropriate demands to act as de facto editors. Before publication too many reporters subserviently offer their stories to the subjects of those stories for what is perversely referred to as "quote approval."

List of Guidelines

In my classes, students are taught to level the playing field with interviewees. We develop a list of guidelines; here are some examples:

- Don't allow a government or business representative who expects to be referred to by his or her official title to refer to the interviewer with only a first name.

- Control the architecture of the interview venue. Don't accept a seat on a low couch while the interviewee choreographs a dominant role behind a massive desk.

- Interrupt answers - with respect and courtesy, of course - if those answers are not responsive to questions and simply serve to obfuscate.

We become Spokespersons

But no matter how equitable we may construct the initial interaction with interviewees, no matter how clever we may be eliciting candid answers from our interview subjects, if we allow them to be the final arbiters of our stories we reduce our role to that of a stenographer. No, that's incorrect. A stenographer accurately records what is said. If we allow interviewees to change quotes because they "misspoke" or decide to "rethink" their position or wish to "restate" their points of view, we become their spokespersons. We lose our integrity as journalists. Ultimately all we can trade on is our credibility over time. And if we sacrifice our professionalism in return for access to the newsmakers, we make ourselves impotent vis-à-vis being critical actors helping balance society's powerbrokers.

Resisting and Refusing

When I taught at fjum last summer, I was shocked to learn how pervasive "quote approval" is here in Austria. Demands for such prior restraint are based on flimsy arguments such as alleged concern that reporters don't misrepresent quoted statements or leave out a critical component of a quote. As bad as this culture of Autorisierung is for Austria, when I returned home to the States I observed a growing trend in my own country of government and business leaders demanding to approve quotes in return for interview access.

"New York Times" reporter Jeremy Peters wrote an explosive story last summer revealing how the Obama campaign demanded approval in return for access. I'm pleased to report that in America journalists are resisting and refusing such demands. "The Times" media critic David Carr quotes the newspaper's managing editor Dean Baquet (presumably without seeking his approval first!): "We encourage our reporters to push back. Unfortunately this practice is becoming increasingly common, and maybe we have to push back harder."

"Quote Approval" is an Anachronism

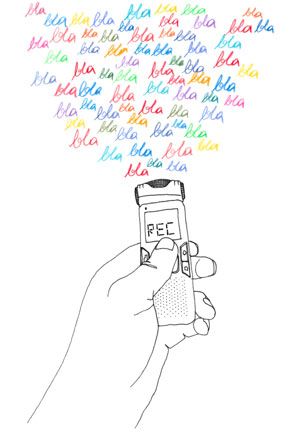

We can win this battle, but only if we fight back. The vast majority of newsmakers would much rather get their sides of any story to the public than disappear from view because their demands for "quote approval" are rejected. We journalists know how to report accurately. News sources can learn how to speak carefully so that they do not need to massage their messages post-interview. Especially in this era of ubiquitous audio recorders (every smart phone is a journalist's Swiss Army knife), "quote approval" is an anachronism that interviewees no longer can hide behind claiming concern about accuracy. We know what they said because their words are recorded.

Austria offers the world spectacular exports, from Sachertorte to Mozart, from Rilke to Klimt's "Kiss" (not to mention the former governor of my home state, California). What the world does not need is Austrian journalism's rigid adherence to "quote approval" demands. And neither does Austria. It's time for journalists hanging out at the Landtmann to look up from their Wiener Melange and tell all the sources who ask for "quote approval," Es tut mir sehr leid, aber ... (Peter Laufer, derStandard.at, 2.5.2013)